Tales My Teacher Told Me: Study Habits That Don’t Actually Work

From the time you enter first grade, your teachers and parents and just about every other adult you know are telling you how to study, thinking that you have study habits that don’t work. Your older brother has notebooks full of highlighted colors cluttering up his desk, and your next-door neighbor mentions that he passed hard tests by spending four or five hours doing nothing but studying for the exam the night before in one long, focused session. Your aunt tells you that she read and re-read her notes and her book to make sure that she was familiar with the materials, while your history teacher tells you to establish one place and one time every night to study, ideally in a quiet place with no distractions.

Researchers, however, have discovered that all of these people, even your teacher (whom you trusted to know better!), are wrong about these study suggestions. In this article, I’ll talk about why these suggested study habits don’t work, and give you four replacements that do.

1. Highlighting.

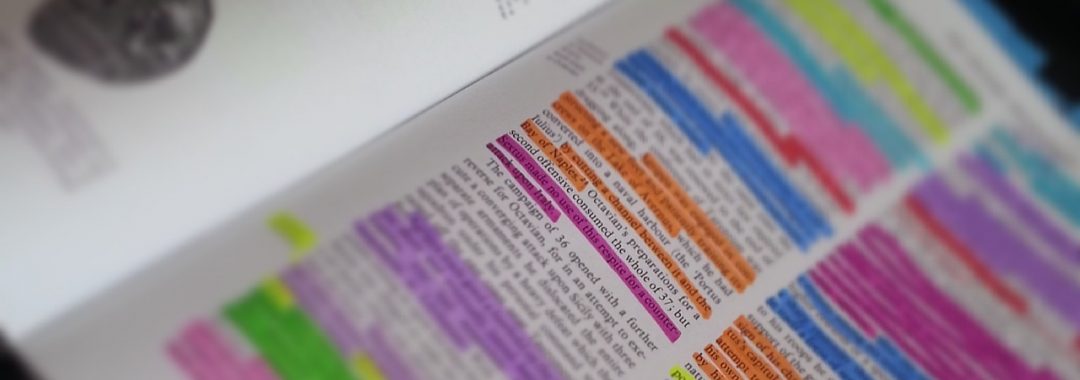

Everyone highlights their books. If you’ve bought a used textbook, it probably came with pages covered in bright yellow, bright pink, and bright blue see-through marker. Students start every semester armed with highlighters, and many depend on them to draw their attention to the important parts of what they’re reading.

But do the highlighted words and ideas actually stick? Researchers at Kent State University tested this idea and found that no, they don’t – and in fact, highlighting everything may make it harder for you to acquire a crucial college skill: the ability to connect one idea to another and see the bigger picture. By focusing you on the individual words, the highlights make it seem to your brain that they don’t go together – that they’re all separate pieces without connection. It’s one of several study habits that don’t work.

New Study Habit/What To Do Instead: Take Notes By Hand

Instead of highlighting, take handwritten notes. Don’t highlight a term and its definition – write it down, by hand, and try to translate it into your own words. Note-taking by hand has been shown to make the Reticular Activation System, the part of your brain that actually remembers stuff for you, to get more active. When you take notes by hand, it increases your focus on the thing you’re taking notes about – and then the Reticular Activation System kicks in and pays better attention to it, too.

2. Reading and Re-Reading

It seems logical that going over the material several times would make it familiar enough that you could remember it, so many students employ the time-consuming method of reading the chapter, and then reading it again, and then reading it again. They might also apply this method to their notes: reading them over and over. Repeated exposure works to help us remember things in other areas of our lives – for example, the more you practice a jump shot, the better you will eventually get – so why is reading and re-reading a study habit that doesn’t work?

In that same study from Kent State, the researchers found that reading does not make it stick. There are three main reasons why, according to Dr. Maryellen Weimer of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

First, students assume that being familiar with the material is the same thing as understanding it. You might know what your car looks like, but unless you have specialized training as a mechanic, you don’t understand how it works beyond the most basic “this is where the gasoline goes” and “this is how to make it go forward, turn, and stop.” In the same way, the sight of the words might feel familiar, but that doesn’t mean you understand what they’re saying.

Second, students assume that time spent on studying is always productive. But your learning isn’t measured by how many minutes or hours you spend on it; it’s measured by how much you can remember and explain. Three hours of thumbing through a familiar textbook isn’t going to help you remember what you’re looking at – you have to become actively engaged with the material.

Finally, the brain doesn’t retain information unless it interacts with it somehow. As Professor Weimer says, “[reading and re-reading] doesn’t result in durable memory.” Re-reading without doing something to actively engage with the material is no better than skimming.

New Study Habit/What To Do Instead: Take Notes on Your Reading

This goes hand-in-hand with taking notes by hand: take them on your reading material as well as in class. But the way you take the notes is very important: divide a piece of paper down the middle (fold it in half long ways, or use a ruler), and take notes only on the right-hand side of the paper. Find the important terms, write them down, and write down a definition in your own words (not the book’s words). On the left-hand side, write questions that might appear on the exam, without their answers. When you study, study the exam questions you’ve written down. Make notes on any you can’t answer; this will tell you what you need to review.

However, you can’t do this if you write the questions and then immediately review them. Write them and set them aside until your next study session, which should be at least 24 to 48 hours away. This brings us to the third study habit that doesn’t work: cramming.

3. Studying in One Long Session (AKA “Cramming”)

Yes, in a list of study habits that don’t work, it might seem like a bit of cheating to include cramming (the practice of studying one subject for a block of three to six hours at once) in a list of study habits that don’t work. But for some students, it seems to work – at least, to pass an exam. The problem is when the student needs to retain or understand the material for something else in the class – for example, a final, or a paper that draws on that material. Cramming is great for short-term memorization, but the problem is that once you’ve dumped out what you forced your mind to retain, it all fades away.

New Study Habit/What To Do Instead: Space Out Your Study Periods

Peter C. Brown and his colleagues showed, in their book Make It Stick, that breaking study into multiple, shorter, spaced-apart blocks is far more effective than studying in one long session. By allowing your brain to rest and sleep between study periods, you create a situation where your brain has to remember what it’s already learned. Every time you study the same material with adequate rest and separation from it in between, you strengthen the connections in your brain that help you retain that information for the long-term.

4. Studying In The Same Conditions Every Time

Have you ever had this experience? You study for an hour or two, so that you’re ready for the questions the professor will ask the next morning. You complete all the readings, take notes, and go to bed confident that you’re ready for the next day. Then you get into class, the professor calls on you, and your mind goes blank.

Why does this happen? Well, as it turns out, the brain makes associations between where you learned something and whether the information is important. So if the only place you’ve studied your history lesson is at your nice, quiet desk in your nice, quiet bedroom with your nice, soft-lit student lamp, then the brain figures that’s the only place you need the information – and when you get into the fluorescent-lit lecture hall, your brain’s not interested in what you learned last night.

Researchers back in 1978 studied this phenomenon and found that when students were given a list of words to study in a clean room with good light and windows, and then studied it again in a cluttered, closed, dim room, they did better on an exam on those words than students who had studied twice in one environment, but not at all in the other.

New Study Habit/What To Do Instead: Study In Different Locations At Different Times

In order to break the association between what you learned and where you learned it, you need to present it to your brain in a number of different environments. Study in your bedroom the first time. The next day, study in a coffee shop. Go out on the campus green and study there, and then take yourself to the library. Eventually, your brain will get the message that it needs this information in more than one place.

Tying It Together

Taking notes by hand may seem like it takes more time than typing or highlighting, and moving from place to place for multiple periods of study may also seem inefficient. But the human brain is not as efficient as our modern world wants it to be. The study techniques that we were told about might seem efficient, but if they don’t make it possible to retain the information, they are actually worse than inefficient – they’re useless.

So work with your brain instead of against it. You’ll remember more, and you’ll remember it longer.

You may also be interested in:

5 Things to Do on the First Day of an Online Course

Why Grades Are Misleading

Why Making Mistakes is Important

4 Ways to Make a Study Schedule Work For You

Which Do You Need: A Coach, or a Tutor?

I agree with everything except your no-highlighting suggestion. However, one can over-highlight and turn the whole page yellow! So I suggested to just highlight 1/4 to 1/3 of the written text.

I definitely like to study in different places. I’m not above working on an essay in the neighborhood bar, in case the bartender is busy, and I don’t have any friends there at that point in time.

Research has found that highlighting doesn’t work very well – underlining works a little better, because you have to look at each word, not just highlight a space. Making notes on the text, of course, tends to work best of all.

I like making notes on articles that are going to be the basis of an essay; highlighting or underlining probably happened first. Sometimes underlining mars the text, especially if it’s with the same pen you’re fixin’ to write with on your next essay! Making notes while listening to a lecture is a very important skill. My new assignment from the Ruist (Confucian) Fellowship is to make a line-by-line commentary on the Great Learning (Ta Hsueh). I better get off the Internet eventually this morning!