Most of the time, high-school students aren’t learning on a deep level. Their learning is usually focused around stuffing in information for tests and then spitting it back out on those tests. They know facts – but they don’t know why they are learning them. It’s just “what the school requires them to learn.”

This is called “surface learning” – looking only at the top level of the topics and focusing on the exams on those topics. At its worst, nothing “sticks.” Students in a surface-learning situation will “cram, jam, and take the exam” – and retain nothing afterward.

That’s not to say that surface learning isn’t necessary – it is! If you don’t know the basic material – the facts and ideas – then it’s impossible to go deep. But too many times, students stop at the surface, hoping to just pick up enough to get through the exams.

When students like this reach college, they’re in for a shock. Sure, some classes are still mostly memorize-and-spit-it-out classes. But more and more, students in college are expected to go deep – to go beyond the facts to analysis, application, and connection. And more and more, students in college haven’t been prepared to go deep into their learning.

How Do You Go Deep?

In 2004, Gene Thompson-Grove developed a three-step protocol for in-class discussions. In this protocol, each person shares what they’re learning or doing, why it matters, and what they need to do next. As they do this, other people give feedback and responses to what the person is doing.

This protocol has since been used in many ways for deeper learning and discussion, from classrooms to boardrooms. The cool thing is, it can also be used to move yourself into deeper learning, whether you have a group or not.

Question 1: What?

In the “What” section of the protocol, you need to talk about the facts. What are you learning? Can you name, define, and describe each of those things?

Think of this section of the protocol as “checking your knowledge.” Perhaps you have to know all the dates of the Revolutionary War, or all of the terms used in a criminal justice class on juvenile delinquency. Maybe you need to know six different equations for your upcoming calculus test, or be able to recognize nine classical musicians by their music for a music appreciation class.

What do you need to know? What are you learning? Can you recognize it when you see it or hear it? How?

Once you’ve nailed down what you’re learning, you can move on to the second step of the protocol.

Question 2: So What?

In this step, you need to start analyzing what you’re learning. Why does it matter? Why should you care? Why is this information important (beyond passing the test on it)? What kind of effects does this information have on the world, or on your understanding of it?

At this level, you’re looking for connection and relationships. How does this information connect up with a problem you’re trying to solve, a question you’re trying to answer, or other fact you’ve learned? Why is it important that it connects in these ways? How does this knowledge relate to other knowledge you’ve received in other places and in other classes?

After you’ve identified how the material you’re learning relates to other material you’ve learned, it’s time to move on to the last step of the protocol.

Question 3: Now What?

Finally, we get to the top of the heap: Now what?

In this step, you begin applying what you’ve learned: How do these facts you’re learning apply to a problem or issue that you’re interested in, or learning about? What might happen if you used the facts in this way, or in that way? Can you predict what would happen if one of the facts were different or had happened differently? What if that fact wasn’t present? What would that do to the overall understanding you have of the topic that the facts are part of?

This is where you start doing application and prediction. How can you use this information to solve a problem? Is it possible to use this information to come up with a new way of understanding what you’ve learned? Are you able to say what will happen next, given what you already know?

This is also the point when you can start critiquing what you’re learning. Does it match up with what you’ve already learned? How does it do that? (Or, conversely, how does it contradict what you’ve learned?) Do you agree with its predictions? What do you think about these connections and applications?

Going Deeper

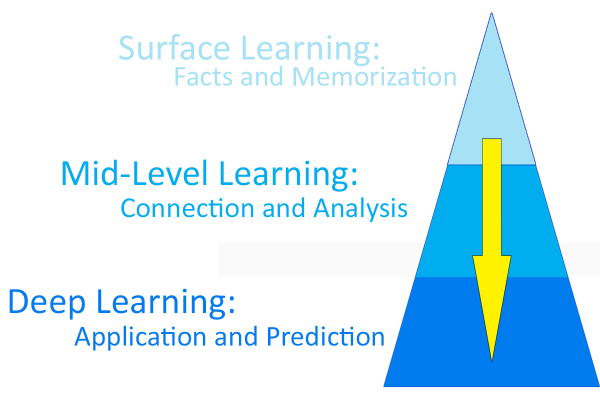

Here’s an overall diagram for what learning looks like when you use this three-question protocol. First, you have surface learning with “What?” Then you get into mid-level learning with “So what?” Finally, you get into the deep learning with “Now what?” At each level, your learning gets richer and more connected, which is critical to building those bridges between your working memory and your long-term memory. The more connections you have, the more bridges you’ve built!

Tying It All Together

When you go deeper, you get better learning. You know more, and it sticks longer than just the exam you have to take. You’ll do better on exams, and feel less stressed about them. You’ll feel more confident about what you know, and more able to investigate what you’re expected to learn. This also helps you with other classes, as you learn to relate what you learned in one class to other classes you’re taking.

Take some time when you’re studying to work on deeper learning. Ask yourself: What? So what? and Now what? and see what happens!